In 1962, the American public’s faith in science was very high. After all, science was credited with helping us win World War II (Spam rations, nylons, the bomb) and was giving an emerging middle-class ever more conveniences and choices.

It was also a time when the answer to many questions was simply: more chemicals.

Certain things had gone unnoticed in this triumphal story, however. The synthetic pesticide DDT had been rushed into battle zones in 1940 in the hopes of defeating the spread of typhus via lice or malaria. Over one million people—thousands in the city of Naples and whole islands in the South Pacific, for example—were “deloused” by DDT dusting.

By 1951, DDT was being deployed by crop dusting planes after it had been cleared for civilian use, eliminating malaria from U.S. households after extensive house-spraying efforts. The Department of Agriculture advocated vigorously for farm use.

When the USDA’s fire ant eradication (not just control) program was rolled out in the Deep South, 20 million acres were sprayed, killing various kinds of wildlife. In these years, consumers had some 6,000 different pesticide products available, with little testing, nor restrictions on use. Meanwhile, more reports of dead birds and fish kept appearing.

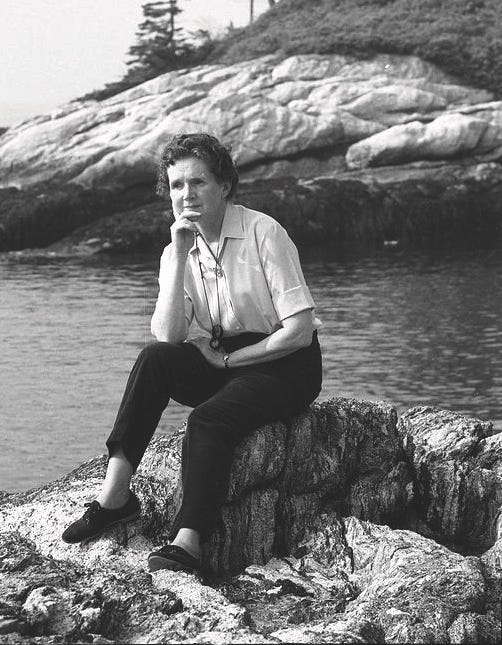

Rachel Carson, the author of the iconic report Silent Spring, resembled her near contemporary Jane Jacobs in being something of a reluctant prophet—but one who was unafraid to question authority (or corporate power), once the time of testing came.

Her first love was the ocean which, as she later noted, came to teach her everything about “the connectedness of the world.” Between 1941 and 1955, she wrote three lyrical books about the sea, at a time when there was little popular knowledge about the subject. Serialized first in the New Yorker, her The Sea Around Us became one of the best-selling science books of all time, translated into 30 languages.

In one of her warm letters to her friend Dorothy Freeman, she explained what was compelling her to write a new—and darker—kind of book: “Everything which meant most to me as a naturalist was being threatened and nothing I could do would be more important.” After books about beauty, she had to write one about death and its causes.

Scientists in this Cold War period were not advocates. But Carson became a crusader, all while fighting the cancer that would take her life shortly after Silent Spring’s publication. She was not against the prudent use of pesticides but against the indiscriminate use of poisons of any kind—including nuclear radiation—which had unanticipated consequences.

Her legacy can be traced in the Environmental Protection Agency (1970), the Safe Water Drinking Act (1974), and the Toxic Substances Control Act (1976), to say nothing of the global environmental movement generally.

Her writings influenced figures like Loren Eiseley, Stephen Hawking, Stephen Jay Gould, Oliver Sacks, James Watson, Jane Goodall, and Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Our conversation about Carson is with her grandnephew and adopted son, Roger Christie, who spent his early years growing up with Carson and learning from her. He is today the chairman of the board of the Rachael Carson Council.

Key takeaways:

A poet of the ocean and in many ways a reluctant prophet—until she felt she had no choice.

While not religious per se, she eventually becomes a social crusader—through her love of the natural world, her humility in the face of beauty.

Her early life resembled Gary Snyder’s: rustic rural with a mother who loved reading.

After years of longing to see the ocean, she gets a job at the Marine Biology Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts—her first sight of the sea. She begins to perceive the interconnectedness of all life.

Her financial struggles: in the Depression years, she becomes her family’s sole breadwinner just as she was about to embark on a PhD at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore.

Her oceanographic work at the Bureau of Fisheries gives her the idea for the first book in what will become her sea trilogy, Under the Sea Wind.

After reading other nature writers, she discovers she has a gift for making the natural world vivid and interesting to readers.

The experience of the Second World War, with its naval ships and submarines, spurred a greater curiosity about understanding the oceans, still little studied or known about at the time.

The wartime success with DDT in defeating malaria boosts its civilian applications, despite its deadly effects on animal and plant populations.

Her literary success finally enabled her to buy a seaside home in Maine where she writes The Sea Around Us and falls in love with a neighbor, Dorothy Freeman. She has also adopted her grandnephew Roger Christie after the death of his mother, her niece.

Her observations about the impact of a chemical barrage destroying habitat and natural ecosystems is part of the first ecological thinking in American public life.

The 1954 H-bomb test over Bikini Atoll puts the phrase “nuclear fallout” into common use—Carson sees it as part of our unwitting self-destruction. Ironically she develops a cancerous condition herself.

Like several other of our Lost Prophets, she resists the technocratic dream of mastering nature instead of simply living within it. This stance brings her under fierce criticism, especially from corporate interests. If Jane Jacobs was an urban naturalist pushing back on the self-appointed experts, Carson is her ecological cousin.

Her heroic final years of illness while completing and speaking about Silent Spring were a race against time.

Timestamps:

00:00—We open the episode with thoughts on Carson's foundational insight: that nature’s balance cannot be overridden without consequence.

05:00–On a Pennsylvania farm, Rachel’s mother instills in her a dual love of nature and writing — the two passions that define her life.

08:00—Forced to take a science requirement in college, Carson falls in love with biology and shifts from aspiring writer to poet scientist.

14:00—Working for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, she publishes a lyrical essay about the ocean in The Atlantic, launching her writing career.

22:00—The Sea Around Us, her second book, becomes a surprise bestseller, bringing national fame and allowing her to leave government work.

26:00—The postwar spread of DDT—once hailed as a miracle chemical—plants the seeds of Carson’s concern as the record of ecological damage grows ever higher.

38:00—Spurred by the alarming data, she begins writing Silent Spring, the book that will make her both famous and controversial.

54:00—Silent Spring is published, followed by a powerful CBS special on Carson and her work. The public rallies to her cause and JFK publicly supports her.

1:00:00—Secretly fighting terminal cancer, she testifies before Congress and inspires the wave of environmental legislation that follows over the next decade and beyond.

1:07:00—Written in 1956 but her final published work, The Sense of Wonder, is an essay written to inspire parents to show their children the wonder of nature.

1:11:00—We interview Roger Christie, Rachel’s grandnephew and adopted son, who offers insights on her work as well as memories of her warmth, humor, and devotion.

1:17:00—Roger describes Carson’s silent suffering with terminal cancer as she was raising him and completing Silent Spring—her final act of service.

1:26:00—We reflect with Roger on how Carson’s ecological worldview applies to today’s crises—from climate change to technocracy.

1:36:00—Final thoughts connecting Carson’s message to those of Jane Jacobs, Wendell Berry, and Abraham Joshua Heschel: start with love, stay rooted in wonder, and resist abstraction.

Recommended:

Under the Sea Wind (1941)

The Sea Around Us (1951)

The Edge of the Sea (1955)

Silent Spring (1962)

The Sense of Wonder (1965)

Rachel Carson (2017)—PBS documentary biography

The Power of One Voice (2014)—documentary on Carson’s legacy